By HeNNy Freitas

(EN) (português abaixo)

If all the people living in ecovillages around the world gathered in a single territory, we would form a city of half a million inhabitants – small compared to the 8.1 billion humans living across more than 2.5 million cities on the planet, yet immense in terms of regenerative impact.

Being at COP 30, the first ever held in the heart of the Amazon, brought this vision to life: for a few days, the city of Belém became a living representation of ecovillages – a diverse, committed movement demonstrating solutions that already work in practice.

And if we could truly see ourselves this way, as a global city spread across hundreds of territories, perhaps we would better understand the power we hold as intentional communities. Throughout plenaries, debates, and crowded corridors at the UN Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC), ecovillage representatives from diverse biomes echoed the forest’s pulsating heart: a reminder that many of the solutions sought in negotiation rooms already exist, and now more than ever, they need to be visible.

These solutions emerge from the grassroots: from traditional, indigenous, and intentional communities – the living territories we call ecovillages. While ecovillages may not yet occupy the main negotiation blocks, they are fertile margins, carrying the responsibility of pragmatic regeneration.

Present on all continents and across more than 114 countries, nearly 60% of the world’s nations, ecovillages and regenerative communities already embody the reality international negotiations strive to achieve: community-based renewable energy, agroecology, edible forests that “plant” water, circular economies that close resource loops, bioconstructions that restore poetry to architecture, and participatory governance that centers relationships and decisions within territorial commons.

If the world embraced this approach, borders would shift from political to bioregional: guided by rivers, winds, and the bonds between people and place. The goal would move beyond “sustainable development” to regenerating interdependent relationships, a vision articulated in a dossier prepared by Brazilian ecovillage leaders.

Ecovillages as Public Policy

Though often seen as a privilege of few, ecovillages function as socio-environmental laboratories: intentionally designed, planned, and built to integrate ecological, social, economic, and cultural dimensions of sustainability in practice, aligned with the Regenerative Development Goals (RDGs) of the Global Ecovillage Network.

Unlike the sustainable development paradigm, focused on reducing negative impacts, regenerative development goes further: it seeks to restore and strengthen living, social, and economic systems. Its pillars include ecosystem regeneration, biodiversity enhancement, local economic empowerment, and the improvement of quality of life based on autonomy and abundance.

Recognized by the UN since the 1990s and implemented as national policy in countries such as Senegal and Togo, ecovillages demonstrate that local solutions can reduce emissions, protect biomes, restore soils, generate income, and strengthen community ties.

The Brazilian dossier presented at COP 30 highlights the urgent need to recognize ecovillages, rural and urban, as legitimate tools for intentionally sustainable occupation. It proposes technical guidelines, legislative adjustments, and the creation of a National Ecovillage Agency to strengthen these communities through regenerative policies in the face of climate collapse.

Ko au te awa. Ko te awa ko au

I had the honor of moderating a panel in the Blue Zone, highlighting the growing trend of Latin American ecovillages, including Aldeia Aratikum of the Instituto Biorregional do Cerrado, that self-declare as “Sanctuaries of Life and Peace in Harmony with Nature” and have transformed their lands into a Conservation Unit through the Private Natural Heritage Reserve (RPPN), reaffirming their commitment to the Rights of Nature, a vision shared by the Latin American ecovillage network CASA Latina and the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN).

This perspective echoes the ancestral wisdom of indigenous peoples, who for millennia have recognized the Earth as a living being, a rights-bearing entity. During COP, I had the privilege of engaging with the Maori of New Zealand and learning about the century-long process that led to the legal recognition of the Whanganui River. In 2017, it became the first river in the world with intrinsic rights, ensuring that its ecosystems and natural entities have the right to exist, flourish, and regenerate, independently of their “utility” to humans.

The Maori maintain a profound spiritual connection with the river, often expressed in the phrase: “Ko au te awa. Ko te awa ko au” – I am the river. The river is me.

If the world could (re)learn to listen to the Earth’s calls – the wind that blows, the water that guides, the forest that breathes – perhaps we would understand that many solutions sought in COPs do not need to be reinvented; they need to be nurtured, strengthened, funded, and respected in their own living logic.

Regenerative Transition

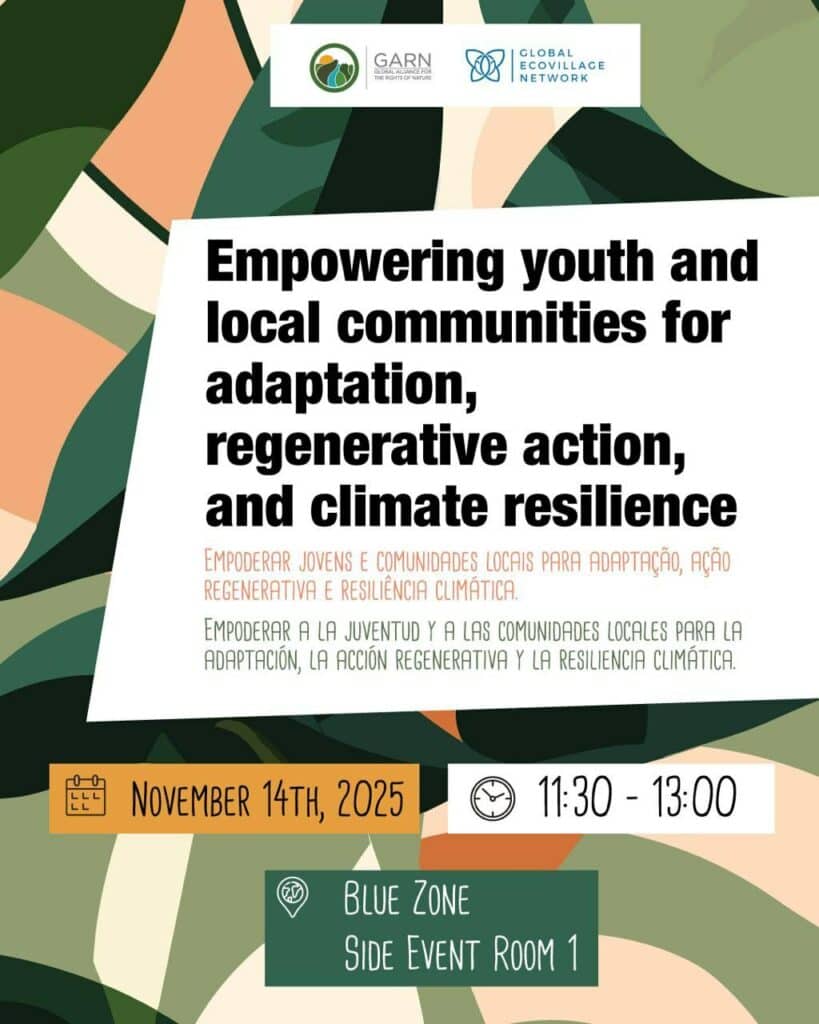

From the panel “Empowering Youth and Local Communities for Adaptation, Regenerative Action, and Climate Resilience” in the Blue Zone, to the discussion circle “The Power of Communities” at Dorothy Stang Square; from the roundtable “We Are Nature” at the People’s Summit to the debate “Ecovillages at COP” in the Free Zone; from the photographic exhibition “From the Andes to the Atlantic: 333 Days on Board an Intentionally Sustainable Adventure” at the People’s Embassy, to sunrise navigation on the Guamá River and the Climate March through Belém — in all spaces of dialogue, the message was clear: the world needs not only an energy transition but a regenerative transition.

To achieve this, it is essential to occupy all territories to remind the world that transition is not only technological: it is spiritual, cultural, relational, and emotional. It demands less consumption and more care; less rhetoric and more practice; less extraction from the Earth and more interconnected relationships among all living systems.

The political results of COP 30 fell short of expectations. Yet every encounter, every word, and every shared vision strengthens a network growing from within — like the roots of the giant Amazonian Samaúma tree, breaking through concrete and pointing toward possible paths of regeneration.

Another way to (re)exist on the planet, more just, more alive, more interdependent, is not only possible: it is already happening!

<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

(PO)

Além das Negociações: Ecovilas como Soluções Climáticas Reais na COP 30

Por: HeNNy Freitas

Se todas as pessoas que vivem em ecovilas ao redor do mundo se reunissem em um único território, formaríamos uma cidade de meio milhão de habitantes — pequena diante dos 8,1 bilhões de seres humanos que habitam as mais de 2,5 milhões de cidades do planeta, mas imensa em termos de impacto regenerativo. Estar na COP 30, a primeira realizada no coração da Amazônia, fez com que essa imagem ganhasse vida: era como se a cidade de Belém recebesse, por alguns dias, a representação viva das ecovilas — um movimento diverso e profundamente comprometido com soluções que já funcionam na prática.

E se de fato nos víssemos assim — uma cidade global espalhada em centenas de territórios —, talvez entendêssemos melhor o poder que carregamos enquanto comunidades intencionais. Na Conferência das Partes da ONU sobre Mudanças Climáticas (UNFCCC) , entre plenárias, debates e corredores lotados, representantes de ecovilas de diferentes biomas deixavam ecoar o coração pulsante da floresta: um lembrete de que parte das soluções buscadas nas salas de negociação já existe e, agora mais do que nunca, precisam ser visibilizadas.

Soluções que vêm da base, das comunidades tradicionais, indígenas e intencionais — dos territórios vivos que chamamos ecovilas. As ecovilas ainda não ocupam os grandes blocos de negociação, mas são margens férteis que carregam consigo a responsabilidade de uma regeneração pragmática.

Presentes em todos os continentes e distribuídas por mais de 114 países — quase 60% das nações do mundo —, ecovilas e comunidades regenerativas vivem hoje a realidade que as negociações internacionais buscam alcançar: energia renovável comunitária, agroecologia e florestas comestíveis capazes de “plantar” água, economias circulares que fecham ciclos, bioconstruções que devolvem poesia à arquitetura, governança participativa que coloca relações e decisões no centro da vida comunitária.

Se o mundo abraçasse essa lógica de mudança, nossas fronteiras deixariam de ser políticas e passariam a ser biorregionais: guiadas pelos rios, pelos ventos e pelos vínculos entre pessoas e território. O propósito deixaria de ser o “desenvolvimento sustentável” para reGENerar relações de interdependências — e é seguindo essa visão de mundo que um dossiê elaborado por lideranças de ecovilas brasileiras foi proposto.

Ecovilas como Políticas Públicas

Embora ainda sejam vistas por muitos como um privilégio de poucos, as ecovilas funcionam como verdadeiros laboratórios socioambientais cujos territórios são intencionalmente desenhados, planejados e construídos para integrar, na prática, as dimensões ecológica, social, econômica e cultural da sustentabilidade, alinhadas aos Objetivos do Desenvolvimento Regenerativo (RDGs, na sigla original) da Rede Global de Ecovilas.

Diferentemente do paradigma do desenvolvimento sustentável — focado na redução de impactos negativos —, o desenvolvimento regenerativo é uma abordagem de planejamento que vai além da sustentabilidade: são práticas que buscam restaurar e fortalecer sistemas vivos, sociais e econômicos. Seus pilares incluem a regeneração de ecossistemas, a ampliação da biodiversidade, o fortalecimento de economias locais e a melhoria da qualidade de vida com base em autonomia e abundância.

Reconhecidas pela ONU desde a década de 1990 e já implementadas como políticas públicas nacionais em países africanos como Senegal e Togo, as ecovilas demonstram que soluções locais reduzem emissões, protegem biomas, restauram solos, geram renda e fortalecem vínculos comunitários.

O dossiê brasileiro apresentado na COP 30 aponta a urgência de reconhecer ecovilas — rurais e urbanas — como instrumentos legítimos de ocupações intencionalmente sustentáveis. Propõe diretrizes técnicas, ajustes legislativos e a criação de uma Agência Nacional de Ecovilas, voltada ao fortalecimento territorial dessas comunidades através do fomento de políticas regenerativas frente ao colapso climático.

Ko au te awa. Ko te awa ko au

Tive a honra de mediar um painel na Zona Azul, destacando a crescente tendência de ecovilas latino-americanas em se autodeclararem “Santuários de Vida e Paz em Harmonia com a Natureza”, reafirmando o compromisso com os Direitos da Natureza — uma visão compartilhada pela rede latinoamericana de ecovilas, CASA Latina, e pela Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN).

Tive a honra de mediar um painel na Zona Azul, destacando a crescente tendência das ecovilas latino-americanas — incluindo a Aldeia Aratikum do Instituto Biorregional do Cerrado — que se autodeclaram “Santuários de Vida e Paz em Harmonia com a Natureza” e transformam suas terras em uma Unidade de Conservação por meio da Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural (RPPN), reafirmando seu compromisso com os Direitos da Natureza — uma visão compartilhada pela rede latino-americana de ecovilas CASA Latina e pela Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN).

Essa perspectiva faz eco à sabedoria ancestral dos povos originários, que há milênios reconhecem a Terra como um ser vivo, sujeito de direitos. Durante a COP, tive o privilégio de (con)viver como o povo Maori da Nova Zelândia e conhecer mais de perto o processo centenário que levou ao reconhecimento jurídico do Rio Whanganui. Em 2017, ele se tornou o primeiro rio do mundo a ter direitos intrínsecos, garantindo que seus ecossistemas e entidades naturais possuam o direito de existir, florescer e se regenerar, independentemente de sua “utilidade” para os seres humanos.

O povo Maori mantém uma conexão espiritual profunda com o rio, frequentemente expressa na frase: “Ko au te awa. Ko te awa ko au” — Eu sou o rio. O rio sou eu.

Se o mundo pudesse (re)aprender a ouvir os clamores da Terra — o vento que sopra, a água que orienta, a floresta que respira — talvez compreendêssemos que muitas das soluções buscadas nas COPs não precisam ser reinventadas: precisam ser fomentadas, fortalecidas, financiadas e respeitadas em sua própria lógica vital.

Transição Regenerativa

Do painel “Empoderando Jovens e Comunidades Locais para a adaptação, ação regenerativa e resiliência climática, na Blue Zone à roda de conversa “Poder das Comunidades”, na Praça Dorothy Stang; da mesa “Nós somos a Natureza”, na Cúpula dos Povos ao debate “Ecovilas na COP”, na FreeZone; da exibição fotográfica “Dos Andes ao Atlântico, 333 dias a bordo de uma aventura intencionalmente sustentável”, na Embaixada dos Povos ao amanhecer navegando o rio Guamá e à Marcha pelo Clima, nas ruas de Belém — em todos os espaços de diálogo, a mensagem é a mesma: precisamos não só de uma transição energética, mas de uma transição regenerativa.

Para isso é crucial seguirmos ocupando todos os territórios para lembrar que a transição não é apenas tecnológica: é também espiritual, cultural, relacional e emocional. É uma transição que exige menos consumo e mais cuidado; menos retórica e mais prática; menos extração da Terra e mais relações interconectadas entre todos os sistemas vivos.

Os resultados políticos da COP 30 ficaram aquém dos esperados. Mas cada encontro, cada palavra e cada visão compartilhada fortalece uma rede que cresce de dentro para fora — como as raízes da gigante Samaúma amazônica, que rompem o concreto e apontam caminhos possíveis em direção à regeneração.

Porque outra forma de (r)existir no planeta — mais justa, mais viva, mais interdependente — não só é possível: ela já está acontecendo!

Leave a Reply